Phases of Data Modeling

- Learn about the logical and physical phases of data modeling

- Compare embedded documents to referenced documents and learn when to use each method

- See best practices for building your data model

A data modeling exercise typically consists of two phases: logical data modeling and physical data modeling. Logical data modeling focuses on describing your entities and relationships. Physical data modeling takes the logical data model and maps the entities and relationships to physical containers.

Logical Data Modeling

The logical data modeling phase focuses on describing your entities and relationships. Logical data modeling is done independently of the requirements and facilities of the underlying database platform.

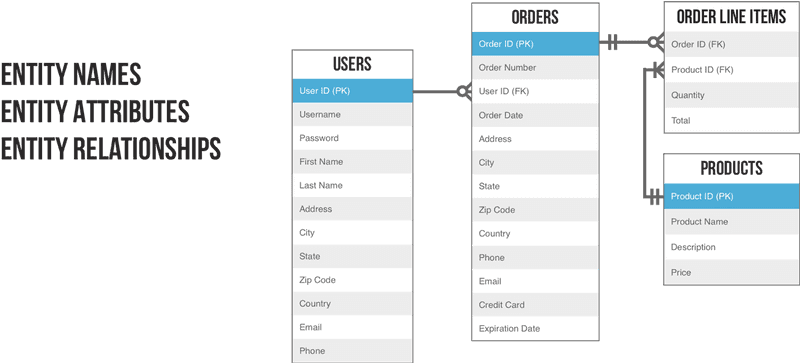

At a high level, the outcome of this phase is a set of entities (objects) and their attributes that are central to your application's objectives, as well as a description of the relationships between these entities. For example, entities in an order management application might be users, orders, order items and products where their relationships might be "users can have many orders, and in turn each order can have many items".

Lets look at some of the key definitions you need from your logical data modeling exercise:

- Entity keys: Each entity instance is identified by a unique key. The unique key can be a composite of multiple attributes or a surrogate key generated using a counter or a UUID generator. Composite or compound keys can be utilized to represent immutable properties and efficient processing without retrieving values. The key can be used to reference the entity instance from other entities for representing relationships.

- Entity attributes: Attributes can be any of the basic data types such as string, numeric, or Boolean, or they can be an array of these types. For example, an order might define a number of simple attributes such as order ID and quantity, as well as a complex attribute like product which in turn contains the attributes product name, description and price.

- Entity relationships: Entities can have 1-to-1, 1-to-many, or many-to-many relationships. For example, "an order has many items" is a 1-to-many relationship.

Analyze your logical model

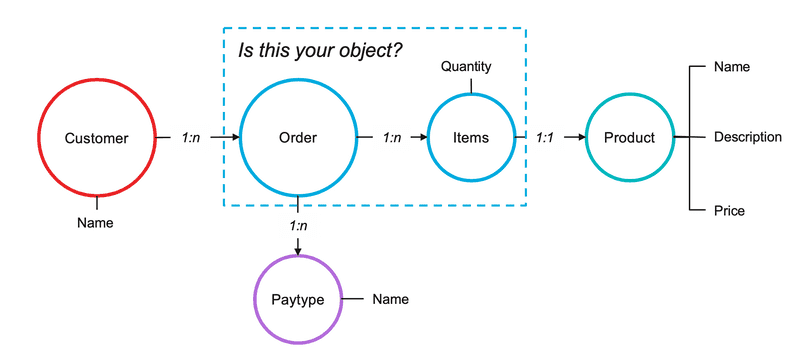

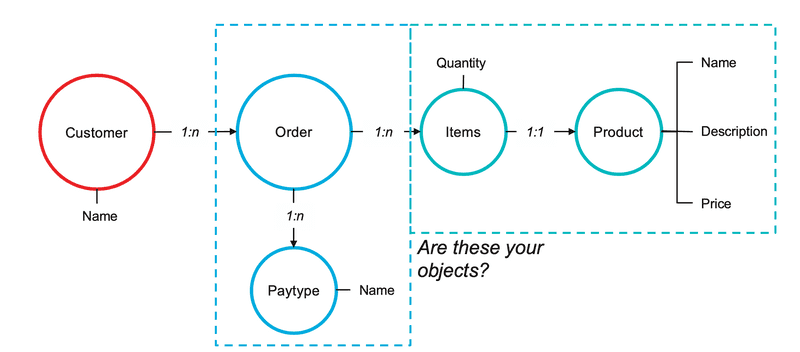

Lets look at a highly simplified Order Management System as an example.

In the below diagram: Order embeds Items, and refs external Product (1:n) and Paytype (1:1) docs.

In the below diagram: Order embeds Paytype and refs Items which embeds Product.

Logical data modeling starts with a decision on how to map your entities to documents. JSON documents provide great flexibility in mapping 1-to-1, 1-to-many or many-to-many relationships.

At one end, you can model each entity to its own document with references to represent relationships. At the other end, you can embed all related entities into a single large document. However, the right design for your application usually lies somewhere in between. Exactly how you should balance these alternatives depends on the access patterns and requirements of your application.

When to Embed & When to Refer

Lets take a look at the example of a stock management system to track Couchbase-branded swag.

Let's imagine the standard path is:

- A customer makes an order.

- A stock picker receives the order and packages the items.

- A dispatcher sends out the package through a delivery service.

At the moment the customer makes an order, we have a choice of how we store the order data in Couchbase:

- either embed all the order information in one document

- or maintain one main copy of each record involved and refer to it from the order document.

Embedding:

If we chose to embed all the data in one document, we might end up with something like this:

{

"orderID": 200,

"customer": {

"name": "Steve Rothery",

"address": "11-21 Paul Street",

"city": "London"

},

"products": [

{

"itemCode": "RedTShirt",

"itemName": "Red Couchbase t-shirt",

"supplier": "Lovely t-shirt company",

"location": "warehouse 1, aisle 3, location 4",

"quantityOrdered": 3

},

{

"itemCode": "USB",

"supplier": "Memorysticks Foreva",

"itemName": "Black 8GB USB stick with red Couchbase logo",

"location": "warehouse 1, aisle 42, location 12",

"quantityOrder": 51

}

],

"status": "paid"

}Here, everything we need to fulfill the order is stored in one document. Despite having separate customer profile and item details documents, we replicate parts of their data in the order document. This might seem wasteful or even dangerous, if you're coming from the relational world. However, it's quite normal for a document database. As we saw earlier, document databases operate around the idea that one document could store everything you need for a particular situation.

There are, though, some trade-offs to embedding data like this.

First, let's look at what's potentially bad:

- Inconsistency: if Steve wants to update his address after the order is made but not shipped, we're relying on:

- our application code to be robust enough to find every instance of his address in the database and update it.

- nothing going wrong on the network, database side or elsewhere that would prevent the update completing fully.

- Queryability: by making multiple copies of the same data, it could be harder to query on the data we replicate as we'll have to filter out all of the embedded copies.

- Size: you could end up with large documents consisting of lots of duplicated data.

- More documents: this isn't a major concern but it could have some impacts, such as the size of your cached working set.

So, what benefits does embedding give us? Mostly, it gives us:

- Speed of access: embedding everything in one document means we need just one database look-up.

- Potentially greater fault tolerance at read time: in a distributed database our referred documents would live on multiple machines, so by embedding we're introducing fewer opportunities for something to go wrong and we're simplifying the application side.

When to embed:

You might want to embed data when:

- Reads greatly outnumber writes.

- You're comfortable with the risk of inconsistent data across the multiple copies.

- You're optimizing for speed of access.

Why are we asking whether reads outnumber writes?

In our example above, each time someone reads our order they're also likely to update the state of the order:

- someone in the warehouse reads the order document and updates the status to Picked, once they're done.

- one of our despatch team reads the document and updates the status to Despatched when the parcel is with the courier.

- when we receive an automated delivery notice from the courier, our application updates the document status to Delivered.

So, here the reads and writes are likely to be fairly balanced.

Imagine, though, that we add a blog to our swag management system and then write a post about our new Couchbase branded USB charger. We'd make two, maybe three, writes to the document while finessing our post. Then, for the rest of that document's lifetime, it'd be all reads. If the post is popular, we could see a hundred or thousand times the number of reads compared to writes.

As the benefits of embedding come at read-time, and the risks mostly at write-time, it seems reasonable to embed all the contents of the blog post page in one document rather than, for example, pull in the author details from a separate profile document.

There's another compelling reason to embed data:

- You actually want to maintain separate, and divergent, copies of data.

In our swag order above, we're using the customer's address as the despatch address. By embedding the despatch address, as we are, we can easily offer the option to choose a different despatch address for each order. We also get a historic record of where each order went even if the customer later changes the address stored in their profile.

Referring:

Another way to represent our order would be to refer to the user profile document and stock item details document but not to pull their contents into the order document.

Let's imagine our customer profiles are keyed by the customer's email address and our stock items are keyed by a stock code. We can use those to refer to the original documents:

{

"orderID": 200,

"customer": "steve@gmail.com",

"products": [

{

"itemCode": "RedTShirt",

"quantityOrdered": 3

},

{

"itemCode": "USB",

"quantityOrder": 51

}

],

"status": "paid"

}When we view Steve's order, we can fill in the details with three more reads: his user profile (keyed by the email address) and the stock item details (keyed by their item codes).

It requires three additional reads but it gives us some benefits:

- Consistency: we're maintaining one canonical copy of Steve's profile information and the stock item details.

- Queryability: this time, when we query the data set we can be more sure that the results are the canonical versions of the data rather than embedded copies.

- Better cache usage: as we're accessing the canonical documents frequently, they'll stay in our cache, rather than having multiple embedding copies that are accessed less frequently and so drop out of the cache.

- More efficient hardware usage: embedding data gives us larger documents with multiple copies of the same data; referring helps reduce the disk and RAM our database needs.

There are also disadvantages:

- Multiple look-ups: this is mostly a consideration for cache misses, as the read time increases whenever we need to read from disk.

- Consistency is enforced: referring to a canonical version of a document means updates to that document will be reflected in every context where it is used.

When to Refer:

Referring to canonical instances of documents is a good default when modeling with Couchbase. You should be especially keen to use referrals when:

- Consistency of the data is a priority.

- You want to ensure your cache is used efficiently.

- The embedded version would be unwieldy.

That last point is particularly important where your documents have an unbound potential for growth.

Imagine we were storing activity logs related to each user of our system. Embedding those logs in the user profile could lead to a rather large document.

It's unlikely we'd breach Couchbase's 20 MB upper limit for an individual document but processing the document on the application side would be less efficient as the log element of the profile grows. It'd be much more efficient to refer to a separate document, or perhaps paginated documents, holding the logs.

General Guidelines on Nest/Refer

| If... | Then Consider... |

|---|---|

| Relationship is 1:1 or 1:many | Nest related data as nested objects |

| Relationship is many:1 or many:many | Refer to related data as separate docs |

| Reads are mostly parent fields | Refer to children as separate docs |

| Reads are mostly parent+child fields | Nest children as nested objects |

| Writes are mostly either parent or child | Refer to children as separate docs |

| Writes are mostly both parent and child | Nest children as nested objects |

Physical Data Modeling

The physical data model takes the logical data model and maps the entities and relationships to physical containers.

In Couchbase, items are used to store associated values that can be accessed with a unique key. Couchbase also provides buckets to group items. Based on the access patterns, performance requirements, and atomicity and consistency requirements, you can choose the type of container(s) to use to represent your logical data model.

The data representation and containment in Couchbase is drastically different from relational databases. The following table provides a high level comparison to help you get familiar with Couchbase containers.

Data representation and containment in Couchbase versus relational databases:

| Couchbase | Relational databases |

|---|---|

| Buckets | Databases |

| Scopes | Schema/namespace |

| Collections | Tables |

| Documents/Items | Rows |

| Index | Index |

Items

Items consist of a key and a value. A key is a unique identifier within the bucket. Value can be a binary or a JSON document. You can mix binary and JSON values inside a bucket.

- Keys: Each value (binary or JSON) is identified by a unique key. The key is typically a surrogate key generated using a counter or a UUID generator. Keys are immutable. Thus, if you use composite or compound keys, ensure that you use attributes that don't change over time.

- Values

- Binary values: Binary values can be used for high performance access to compact data through keys. Encrypted secrets, IoT instrument measurements, session states, or other non-human-readable data are typical cases for binary data. Binary data may not necessarily be binary, but could be non-JSON formatted text like XML, String, etc. However, using binary values limits the functionality your application can take advantage of, ruling out indexing and querying in Couchbase as binary values have a proprietary representation.

- JSON values: JSON provides rich representation for entities. Couchbase can parse, index and query JSON values. JSON provide a name and a value for each attribute. You can find the JSON definition at RFC 7159 or at ECMA 404. These type of items are typically called "documents".

The JSON document attributes can represent both basic types such as number, string, Boolean, and complex types including embedded documents and arrays. In the examples below, a1 and a2 represent attributes that have a numeric and string value respectively, a3 represents an embedded document, and a4 represents an array of embedded documents.

{

"a1":number,

"a2":"string",

"a3":{

"b1":[ number, number, number ]

},

"a4":[

{ "c1":"string", "c2":number },

{ "c1":"string", "c2":number }

]

}